The National Football League (NFL) is in the hot seat again. This time, players and coaches are accusing the league of racial discrimination in hiring practices for coaches; more specifically, they claim that the NFL is biased against Black personnel for coveted coaching positions. In a sports league where most players are Black, most head coaches are white—and this is the problem.

The National Football League (NFL) is in the hot seat again. This time, players and coaches are accusing the league of racial discrimination in hiring practices for coaches; more specifically, they claim that the NFL is biased against Black personnel for coveted coaching positions. In a sports league where most players are Black, most head coaches are white—and this is the problem.

Despite the fact that 70 percent of NFL players are Black, only one of the 32 head coaches is Black, as of the date of this posting. Recently, there were two other Black head coaches, Brian Flores of the Miami Dolphins and David Culley of the Houston Texans, but both were fired at the end of the season. Their exits left just one Black head coach (Mike Tomlin of the Pittsburgh Steelers) and one Latino head coach (Ron Rivera of the Washington Commanders) in the entire NFL. The rest of the head coaches are white.

On February 2, Flores sued the NFL and three of its teams for discriminatory hiring practices. The lawsuit outlines a series of specific experiences Flores had during his time as a coach in the league.

The NFL and the teams in question have denied these accusations, stating that the absence of Black head coaches is due to a lack of qualified candidates—a claim not supported by the available research. Some coaches and players believe the NFL is purposely overlooking qualified Black candidates to maintain its all-white leadership.

This isn’t the first time that the NFL has been accused of racism; the league has a long history of discriminating against Black athletes and coaches. In 1921, Fritz Pollard became the first coach of color in the NFL, but it took almost 70 years before Art Shell would become the second coach to break down the same barrier. In 2021, coach Jon Gruden was fired following a release of messages containing racist and homophobic remarks. And the topic of race has been a hot-button issue since 2016, when Colin Kaepernick first took a knee during the national anthem to protest racism in America. He has not been able to find a team to work with ever since. The following year, the 32 NFL team owners created a policy that would lead to a player being fined for kneeling during the anthem.1 Some people believe these instances demonstrate that race is an issue that the NFL continues to ignore.

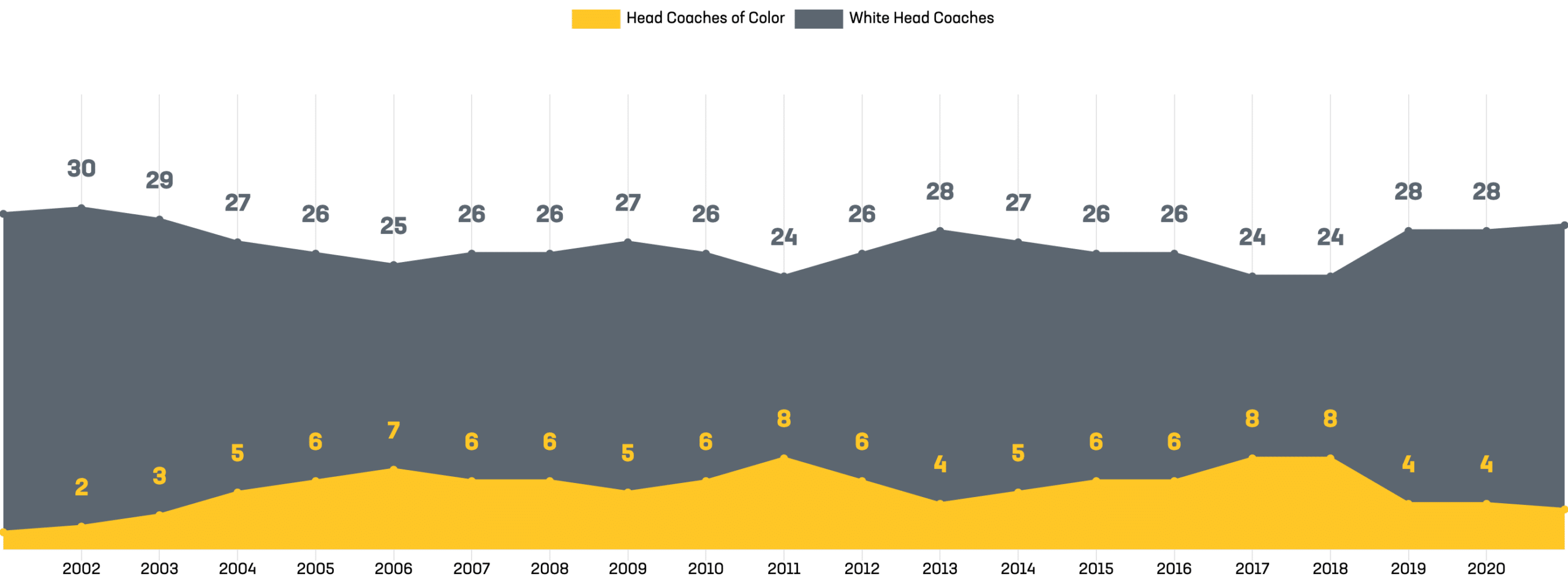

In 2003, the NFL adopted the so-called Rooney Rule to address the league’s lack of diversity in coaching. As of May 2020, the Rooney Rule has been expanded to require teams to interview at least two external minority candidates for their head coaching job and at least one external minority candidate for any coordinator job.2 When the rule was first adopted, there were some positive effects in the short term: the NFL did see an increase in Black and Latino coaches. However, following those initial gains, the number of head coaches of color decreased over time. As of this writing, there are fewer Black head coaches in the NFL than there were in 2003 (when there were three).3

These figures show snapshot comparisons of newly hired NFL head coaches broken down by race in 2002-2003 vs. 2019-2020

Many people in the industry have refused to speak openly with reporters about the alleged discriminatory hiring practices for fear of backlash. However, one person did tell NFL.com that Flores’s case is “probably going to air out a lot of dirty laundry. What happened to [Flores] has been going on for decades, but no one has ever wanted to push the issue. Most have been happy to have the opportunity to work in the league and haven’t wanted to walk away from that opportunity. I admire his resolve.”4

Flores said in an interview that he felt the need to bring this issue to court (despite the negative impact it might have on his career) because “we need change. I know many capable Black coaches who would go out and do a great job on their interviews when given the opportunity. I hate to see that go to waste. We need to change the hearts and minds of the people making the decisions … the white NFL team owners.”5

In his lawsuit documents, Flores says that “the racial discrimination has only been made worse by the NFL’s disingenuous commitment to social equity.”6 He also describes several interviews with the NFL in detail, calling them “sham interviews” meant to fulfill the Rooney Rule requirement and check a box. In his lawsuit, Flores describes the Rooney Rule as well-intentioned but ineffective.

“However, well-intentioned or not, what is clear is that the Rooney Rule is not working. It is not working because the numbers of Black Head Coaches, Coordinators, and Quarterback Coaches are not even close to being reflective of the number of Black athletes on the field. The Rooney Rule is also not working because management is not doing the interviews in good faith. Therefore, it creates a stigma that interviews of Black candidates are only being done to comply with the Rooney Rule rather than in recognition of the talents that the Black candidates possess.”7

So what do Flores and others around the league hope to see the NFL do to bring about change? Here are just a few suggestions they have offered.8

- Increase Black team ownership

- Consistently enforce hiring policies

- Hire a trustworthy external oversight firm

- Commit to greater transparency

- Include players in the hiring process

- Embrace different styles of coaching excellence

- Create head-coaching pathway programs

- Commission a systemic study of the league

- Unionize

READ the full interview for more details on these solutions.

In the end, the NFL must show that it is not biased against Black athletes and coaches or else continue to face the consequences. The longer these issues remain unaddressed, the worse the results could be for the league. What would the NFL do if players and coaches chose to boycott games or file additional lawsuits? Either way, the NFL’s reputation is on the line … again.

Discussion Questions

- Do you think business owners and employers should have the right to refuse to hire someone on the basis of any grounds they choose? Why or why not?

- From what you have read, do you believe the NFL and its teams are doing enough to create diversity among the coaching staff in the league? Why or why not?

- If you were the owner of an NFL team, how would you go about hiring to make sure the most qualified candidates were being hired and that the opportunities were not impacted by race?

Additional Resources

As always, we encourage you to join the discussion with your comments or questions below!

Sources

Featured Image Credit: Doug Murray/AP

[1] Washington Post: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/posteverything/wp/2018/05/24/there-would-be-no-nfl-without-black-players-they-can-resist-the-anthem-policy/

[2] CBS Sports: https://www.cbssports.com/nfl/news/rooney-rule-enhancement-nfl-to-require-two-external-minority-interviews-for-gm-coordinator-jobs/

[3] Texas A&M University: https://today.tamu.edu/2022/01/24/why-most-nfl-head-coaches-are-white-behind-the-nfls-abysmal-record-on-diversity/

[4] National Football League: https://www.nfl.com/news/brian-flores-lawsuit-reflects-widespread-discontent-among-black-coaches-over-nfl

[5] ESPN: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zS5f_YH3Y2A

[6] Wigdor Law: https://www.wigdorlaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Complaint-against-National-Football-League-et-al-Filed.pdf

[7] Ibid.

[8] Rolling Stone: https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/brian-flores-nfl-super-bowl-racism-hiring-coaches-1299131/

Last month, Senators Jon Ossoff, D-Ga., and Mark Kelly, D-Ariz., introduced the Ban Congressional Stock Trading Act, a reform bill that would require members of Congress to divest their stock market investments or face fines totaling the entire amount of their congressional salary.1 So, should members of Congress be allowed to trade stocks?

Last month, Senators Jon Ossoff, D-Ga., and Mark Kelly, D-Ariz., introduced the Ban Congressional Stock Trading Act, a reform bill that would require members of Congress to divest their stock market investments or face fines totaling the entire amount of their congressional salary.1 So, should members of Congress be allowed to trade stocks? On February 4, the Republican National Committee (RNC) officially censured two members of the party, Representatives Liz Cheney, R-Wyo., and Adam Kinzinger, R-Ill., for their role in the ongoing House of Representatives investigation into the Capitol riot that occurred on January 6, 2021.

On February 4, the Republican National Committee (RNC) officially censured two members of the party, Representatives Liz Cheney, R-Wyo., and Adam Kinzinger, R-Ill., for their role in the ongoing House of Representatives investigation into the Capitol riot that occurred on January 6, 2021. President Joe Biden has ordered the Pentagon to put 8,500 U.S. troops on heightened alert for a possible deployment to Europe.1 And the State Department has told the families of U.S. diplomats in Ukraine to leave the country as the possibility of a Russian invasion increases.2 So, what is the situation in Ukraine?

President Joe Biden has ordered the Pentagon to put 8,500 U.S. troops on heightened alert for a possible deployment to Europe.1 And the State Department has told the families of U.S. diplomats in Ukraine to leave the country as the possibility of a Russian invasion increases.2 So, what is the situation in Ukraine? It’s official: 2021 was either the fifth or sixth hottest year on record, depending on who you ask.

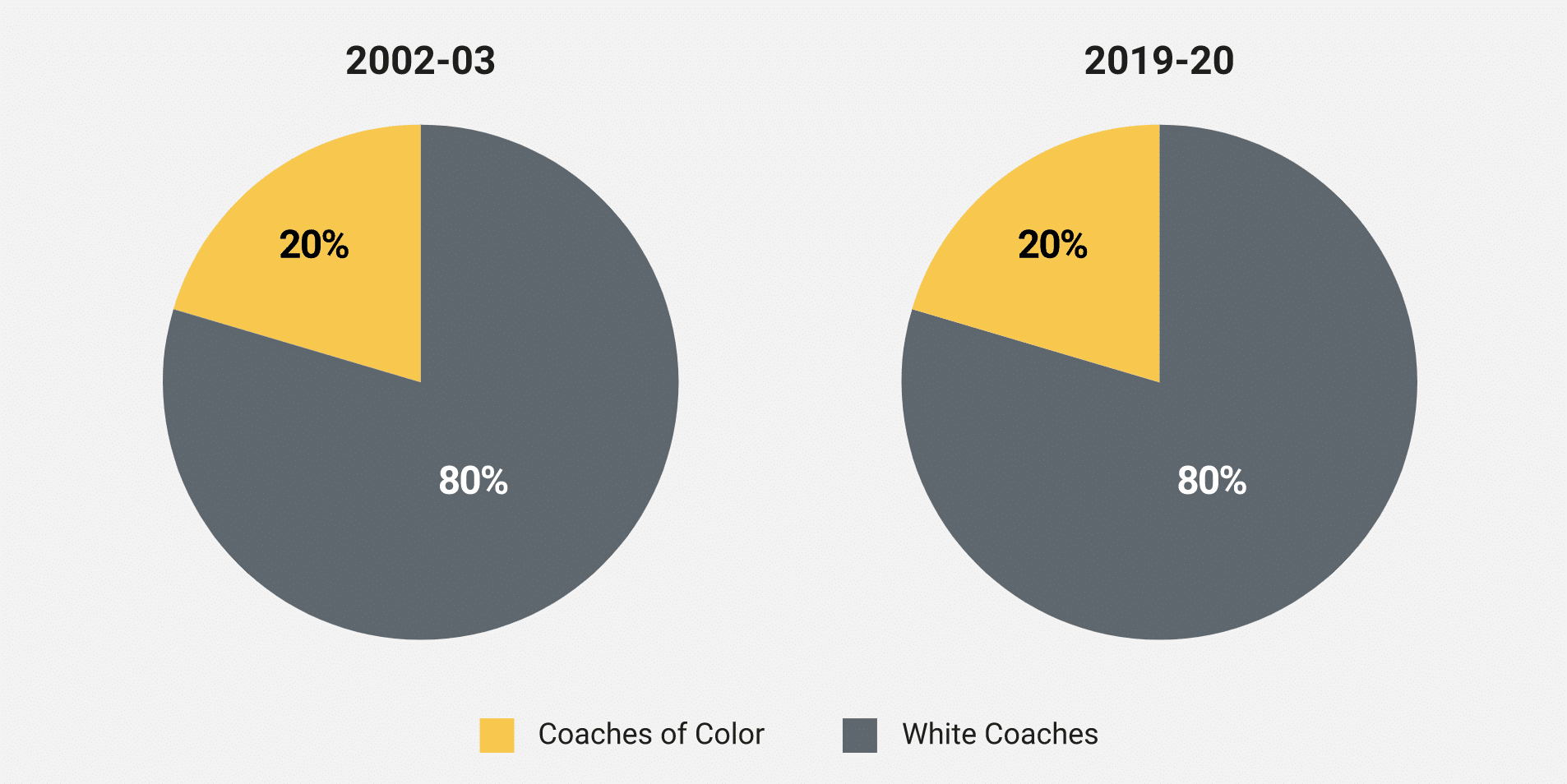

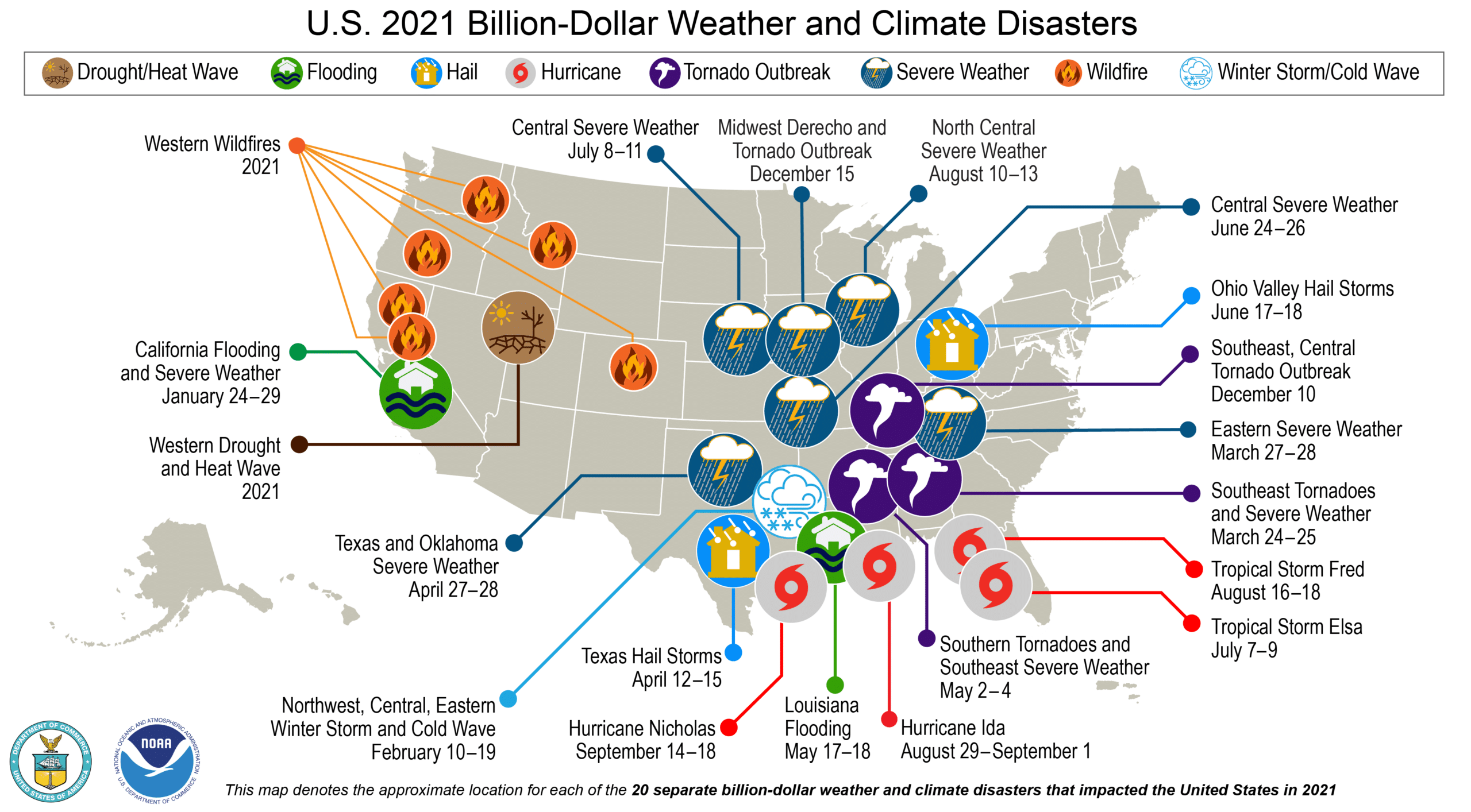

It’s official: 2021 was either the fifth or sixth hottest year on record, depending on who you ask. This is part of a broad trend of record-breaking temperatures. The previous seven years have been the seven hottest on record.5 And according to the NOAA, July 2021 was the single hottest month ever recorded.6 NOAA administrator Rick Spinrad characterized this data as a continuation of “the disturbing and disruptive path that climate change has set for the globe.”7

This is part of a broad trend of record-breaking temperatures. The previous seven years have been the seven hottest on record.5 And according to the NOAA, July 2021 was the single hottest month ever recorded.6 NOAA administrator Rick Spinrad characterized this data as a continuation of “the disturbing and disruptive path that climate change has set for the globe.”7

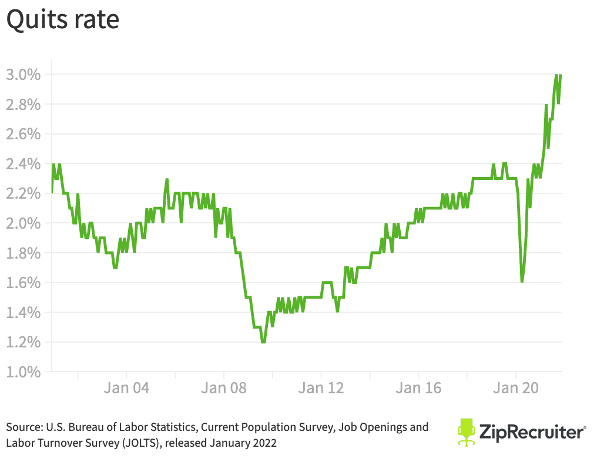

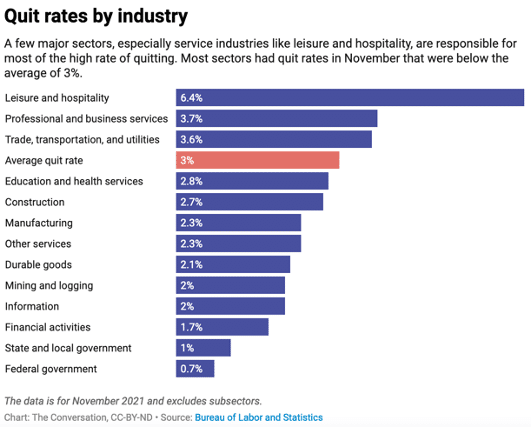

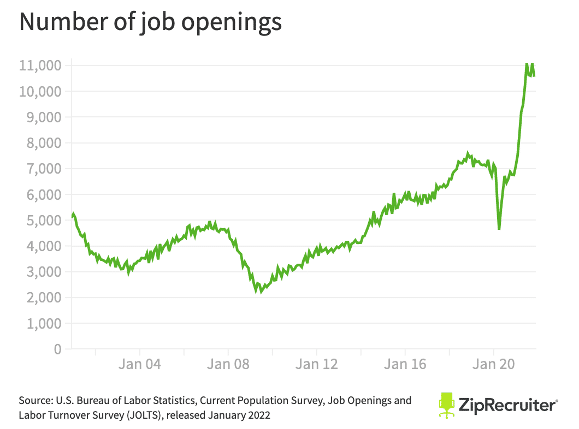

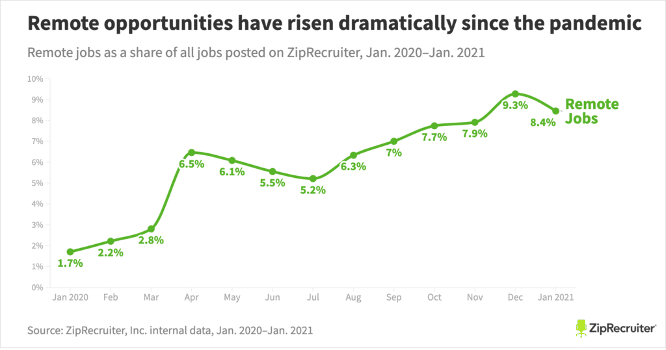

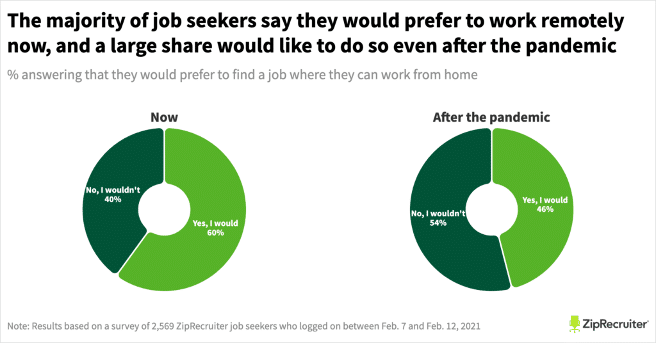

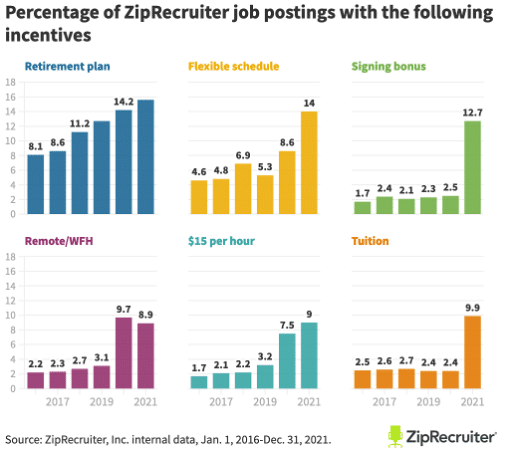

Across the United States, towns and cities are flooded with “Help Wanted” signs on business doors. The U.S. job market has seen its share of ups and downs over the last two years, but 2021 was a year of record-breaking highs in many categories. The two most important: record-breaking quits and record-breaking new job openings.

Across the United States, towns and cities are flooded with “Help Wanted” signs on business doors. The U.S. job market has seen its share of ups and downs over the last two years, but 2021 was a year of record-breaking highs in many categories. The two most important: record-breaking quits and record-breaking new job openings.

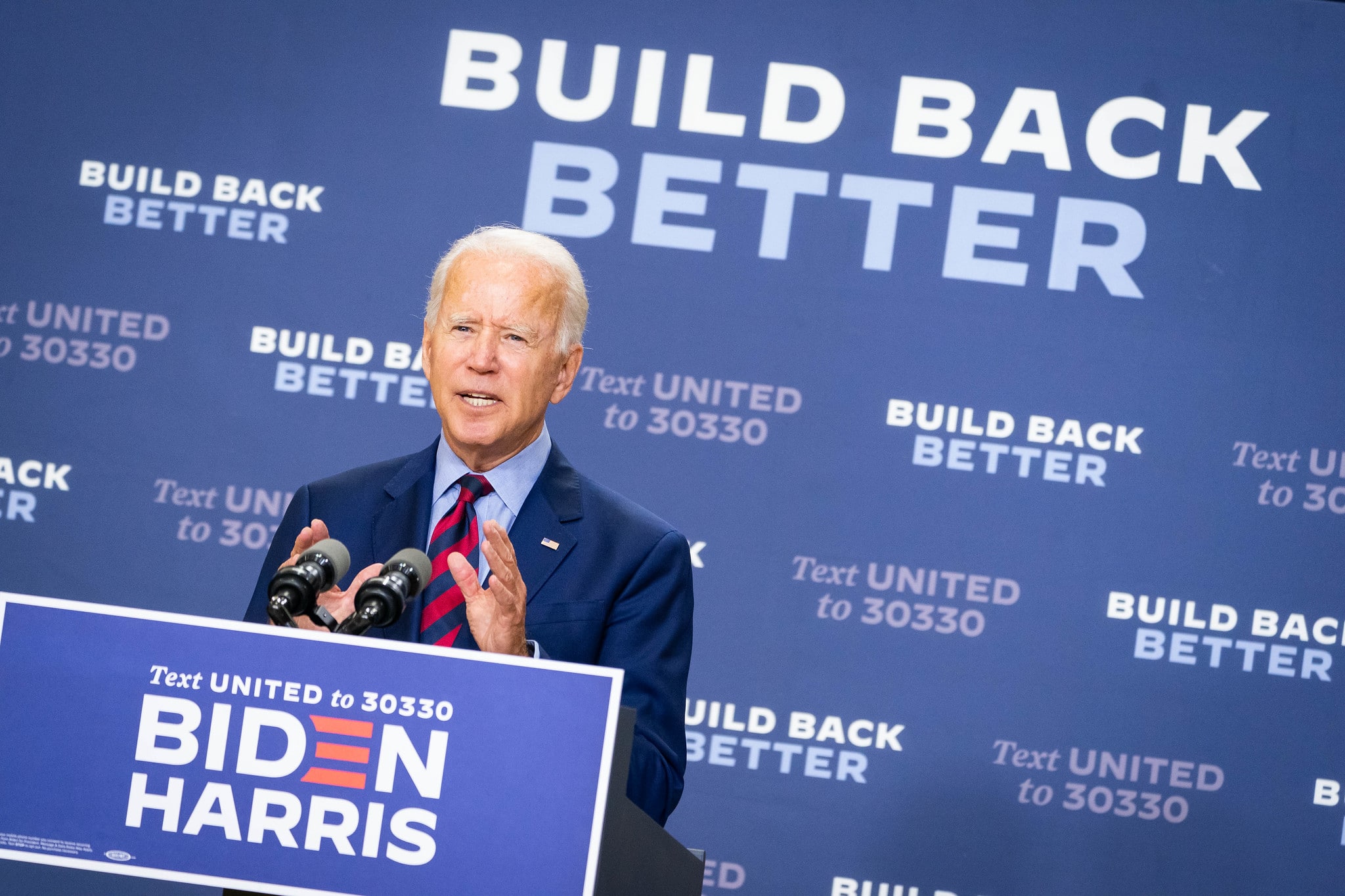

Already facing the enormous challenge of addressing spiking cases of COVID-19 due to the Omicron variant, President Joe Biden’s administration was presented with a new challenge when Senator Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., announced that he would not support the $2 trillion spending plan known as Build Back Better Bill. Citing concerns over the level of spending on social safety net programs and climate policies, Manchin said he could not find a way to support the bill that would be consistent with what he believes his constituents in West Virginia want.1

Already facing the enormous challenge of addressing spiking cases of COVID-19 due to the Omicron variant, President Joe Biden’s administration was presented with a new challenge when Senator Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., announced that he would not support the $2 trillion spending plan known as Build Back Better Bill. Citing concerns over the level of spending on social safety net programs and climate policies, Manchin said he could not find a way to support the bill that would be consistent with what he believes his constituents in West Virginia want.1 On November 26, 2021, the World Health Organization announced the discovery of a new COVID-19 variant in South Africa. The same day, President Joe Biden closed the borders to travelers from South Africa and seven nearby nations (Namibia, Botswana, Lesotho, Eswatini, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Malawi) in the hope of slowing the spread of the variant to the United States. In a speech to the American public on November 29, President Biden addressed the closing of the border, saying, “Closing the borders cannot prevent the spread, but … it gives us time to take more actions, to move quicker, for people to get the vaccine.”

On November 26, 2021, the World Health Organization announced the discovery of a new COVID-19 variant in South Africa. The same day, President Joe Biden closed the borders to travelers from South Africa and seven nearby nations (Namibia, Botswana, Lesotho, Eswatini, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Malawi) in the hope of slowing the spread of the variant to the United States. In a speech to the American public on November 29, President Biden addressed the closing of the border, saying, “Closing the borders cannot prevent the spread, but … it gives us time to take more actions, to move quicker, for people to get the vaccine.”