In communities across the country, teachers are welcoming students back to school as the summer draws to a close. The beginning of the school year is an exciting and important time for establishing good civic habits in students. To help facilitate dialogue among students and spark civil discussion in the classroom, we are reviewing several noteworthy summer 2022 news.

Roe v. Wade 2022 Overturned

In late June, the Supreme Court issued its decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, essentially overturning the precedent of Roe v. Wade (1973).1 Over the summer, Close Up students joined with our partners at A Starting Point to discuss the impact of the Dobbs decision with New York University law professor Melissa Murray.

READ: Close Up-ASP Homeroom Resource: After Roe v. Wade

The policy landscape regarding reproductive rights is still shifting, as state legislatures, courts, doctors, and other institutions figure out their next steps. There are many policies being considered in states across the country, and there are new lawsuits emerging as well. Not all of these debates will be strictly about access to abortion. For example, there may be debates about supporting women during their pregnancies and supporting families after children are born. “[Women] are far less likely to have assistance for themselves and their children, and they are far less likely to have health care available to them when they are pregnant and for their children,” says Stuart Butler, a researcher with the Brookings Institution. “And that means that there’s going to be not only more hardship, but greater health problems and maternal deaths and so on … unless there is a fundamental change in political behavior in those states.”2

The Midterm Election Primaries

This year is a congressional election year, with the midterm elections approaching on November 8, 2022. Conventional wisdom suggests this will be a difficult year for Democrats in Congress. The president’s party often loses ground in midterm elections, and this pattern certainly held true in 2006, 2010, and 2018.3 In fact, the 2002 midterms—only a year after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001—are the only midterms since 1946 in which the president’s party did not lose at least some ground in Congress.4

VIEW: The New York Times Primary Election Calendar

Currently, Democrats hold a narrow majority in the Senate, thanks to two independents who caucus with the Democratic Party—Senators Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Angus King (I-Maine)—and the tiebreaking vote of Vice President Kamala Harris. In the House of Representatives, Democrats hold a slightly more substantial majority (220–211 with four vacant seats).5

Early in this election cycle, Republicans appeared poised to win control of both chambers of Congress.6 However, the outlook is no longer quite so clear. This is due in part to the decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization discussed above, as most Americans (61 percent in a 2022 Pew Research Center poll) say abortion should be legal in all or most cases.7 Another issue that seems to be moving somewhat in Democrats’ favor is the fact that gasoline prices are no longer surging, although prices at the pump and overall inflation do remain high.8

While this is a national picture, local social issues for discussion and individual candidates also matter. In recent weeks, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) openly worried about the quality of candidates that won Republican Senate primaries.9

The FBI, the National Archives, and Donald Trump

In early August, the Federal Bureau of Investigation executed a search warrant at former President Donald Trump’s Florida residence. Agents removed several boxes of material from the property, marking the first time in U.S. history that a former president’s home was searched as part of a criminal investigation.10 The FBI, with President Trump’s search warrant, sought to find and secure potentially classified documents that were being held—possibly in violation of federal law—on his property.

The dispute centers around classified documents that some intelligence experts are concerned could put covert agents at risk.11 The National Archives and Records Administration had been involved in a protracted dispute with the former president as it attempted to recover documents. Beginning at least as early as May 2021, the National Archives was in communication with the former president’s legal team in an effort to recover those documents.12

It is unclear what will become of this investigation. There is a possibility that President Trump or others in his orbit will face criminal charges, but this is by no means guaranteed.13 There are other investigations underway relating to the January 6 attack on the Capitol, efforts to overturn election results in Georgia, and the Trump family’s businesses, among other things.14 Against this backdrop, President Trump is also weighing whether and when to announce a run for the presidency in 2024.15 The former president remains at the center of the Republican Party—candidates he has endorsed have won 95 percent of their primary races.16

In the contentious atmosphere of recent U.S. politics, the combination of investigations and congressional and presidential campaigns could be volatile.

Questions for Teachers

- What issues are your students most interested in discussing at the beginning of this school year?

- What issues are you most eager to discuss? What are you apprehensive about discussing?

- How are you planning to teach the 2022 election?

As always, we encourage you to join the discussion with your comments or questions below.

Sources

Featured Image Credit: Justin Hicks/IPB News

[1] ScotusBlog: https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/dobbs-v-jackson-womens-health-organization/

[2] WAMU/NPR: https://wamu.org/story/22/08/18/states-with-the-toughest-abortion-laws-have-the-weakest-maternal-supports-data-shows/

[3] FiveThirtyEight: https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/why-the-presidents-party-almost-always-has-a-bad-midterm/

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ballotpedia: https://ballotpedia.org/United_States_Congress_elections,_2022

[6] CBS News: https://ballotpedia.org/United_States_Congress_elections,_2022

[7] Pew Research: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/fact-sheet/public-opinion-on-abortion/

[8] U.S. News & World Report: https://www.usnews.com/news/the-report/articles/2022-08-05/republican-prospects-for-midterm-pickups-dim-amid-democratic-wins

[9] The Hill: https://www.usnews.com/news/the-report/articles/2022-08-05/republican-prospects-for-midterm-pickups-dim-amid-democratic-wins

[10] ABC News-Chicago: https://abc7chicago.com/donald-trump-maralago-fbi-search-classified-documents/12175658/

[11] CNN: https://www.cnn.com/2022/08/23/politics/national-archives-classified-docs/index.html

[12] ABC News-Chicago: https://abc7chicago.com/donald-trump-maralago-fbi-search-classified-documents/12175658/

[13] USA Today: https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/laws-cited-in-trump-search-warrant-rarely-lead-to-charges-in-trumps-case-experts-say-they-might/ar-AA11bBBT#image=AA10whb5|8

[14] CNN: https://www.cnn.com/2022/08/12/politics/trump-lawsuit-and-investigations-rundown/index.html

[15] NPR: https://www.npr.org/2022/08/24/1118946905/trump-pac-money-fec

[16] FiveThirtyEight: https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/trumps-endorsees-have-started-losing-more-but-dont-read-into-that-for-2024/

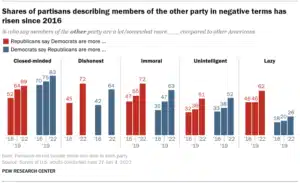

We do not have to look far to find evidence of strong partisan hostility in the United States. People are ending long-term friendships, or even cutting off communication with family, over political discord.

We do not have to look far to find evidence of strong partisan hostility in the United States. People are ending long-term friendships, or even cutting off communication with family, over political discord.

In an interactive photo essay for the

In an interactive photo essay for the

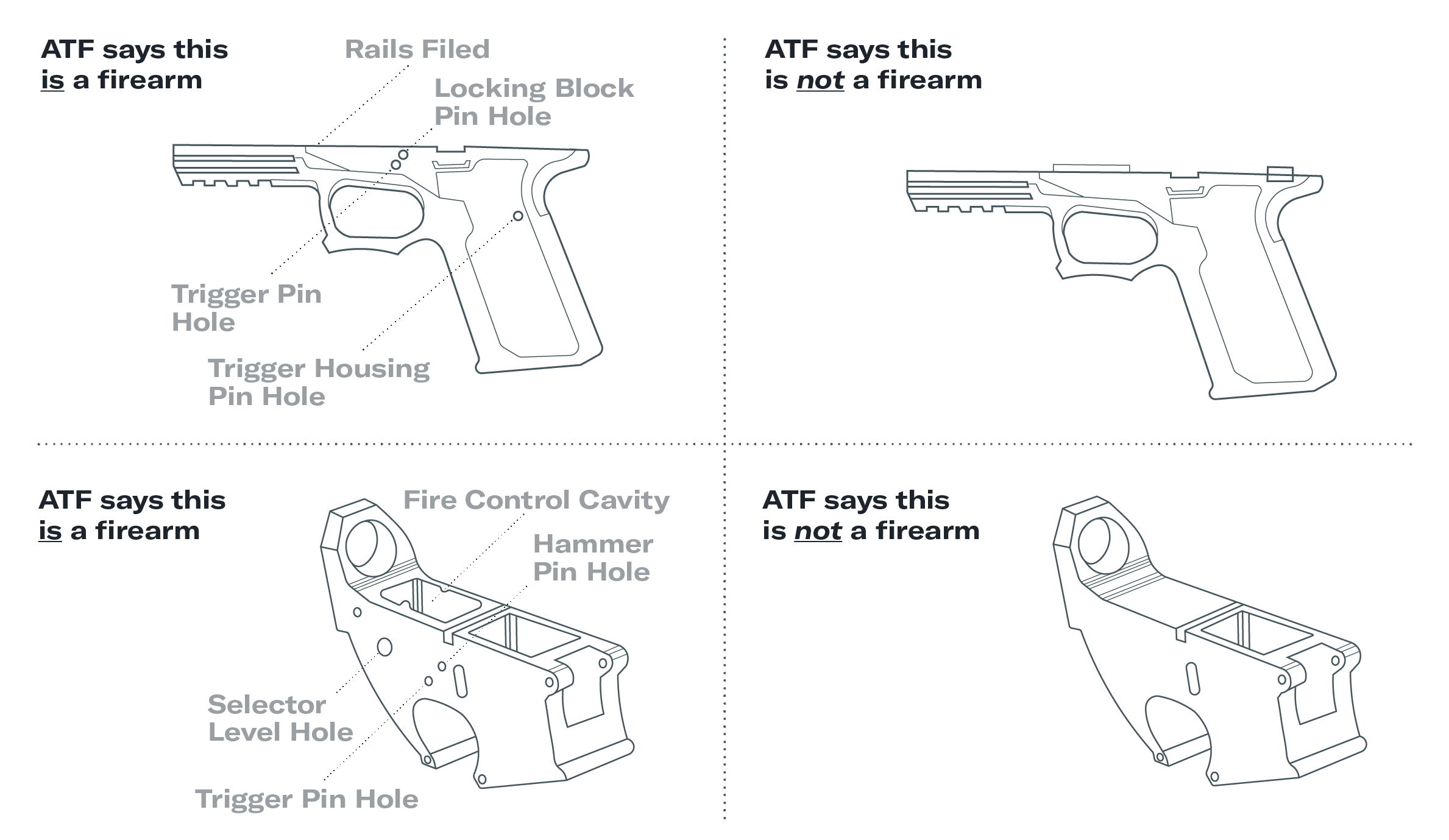

Early last week, President Joe Biden and Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco announced a final ruling to limit the manufacture and sale of so-called “ghost guns”—privately manufactured firearms without serial numbers.

Early last week, President Joe Biden and Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco announced a final ruling to limit the manufacture and sale of so-called “ghost guns”—privately manufactured firearms without serial numbers.

On February 22, Texas Governor Greg Abbott ordered the state Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) to investigate gender-affirming medical care provided to transgender youth as child abuse, requiring mandated reporters (such as teachers, doctors, and health care workers) to pass on that information to the DFPS.1

On February 22, Texas Governor Greg Abbott ordered the state Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) to investigate gender-affirming medical care provided to transgender youth as child abuse, requiring mandated reporters (such as teachers, doctors, and health care workers) to pass on that information to the DFPS.1

On January 26,

On January 26,