Diversity, Discord & Democracy

August 24, 2022 by

We do not have to look far to find evidence of strong partisan hostility in the United States. People are ending long-term friendships, or even cutting off communication with family, over political discord.1 Partisan animosity—feelings of anger, fear, and distrust toward those with whom we disagree—has been steadily increasing for decades.2

We do not have to look far to find evidence of strong partisan hostility in the United States. People are ending long-term friendships, or even cutting off communication with family, over political discord.1 Partisan animosity—feelings of anger, fear, and distrust toward those with whom we disagree—has been steadily increasing for decades.2

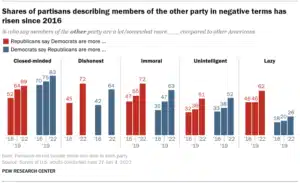

Earlier this month, the Pew Research Center released new survey data that help to give a sense of the problems we face with diversity and democracy. “Perhaps the most striking change is the extent to which partisans view those in the opposing party as immoral,” wrote the report’s authors.3

As the chart below indicates, people believe that members of the opposite party are closed-minded, dishonest, immoral, unintelligent, and lazy.

The fact that large majorities of members of both parties view members of the opposite party as closed-minded and dishonest means that we are lacking fertile ground for deliberative democracy and civil discourse.

While schools alone cannot solve political discord, and schools certainly didn’t create these problems, schools remain a setting in which people from different backgrounds come together for significant stretches of time. Schools can make use of this diversity by facilitating social and political dialogue about pressing issues.4

We encourage teachers to design high-quality political dialogue and deliberations that call on students to weigh evidence from multiple sources, view issues from multiple perspectives, and work collaboratively to solve problems. This blog and our many resources in the Current Issues Resource Library are designed to help teachers foster this kind of dialogue that tackles diversity and democracy.

Related Post: Deliberating About Pressing Issues

Such political dialogue can help students build knowledge and skills, but it is also important for students to reflect on their developing dispositions. There are many dispositions democratic citizens should develop, including:

- Public-Mindedness or a Concern for the Common Good: In addition to thinking about their own needs and desires, citizens must also consider the common good—the needs of others in society—when making decisions.5

- Humility and Open-Mindedness: Humility involves understanding that one’s knowledge and experiences are not the only knowledge, opinions, or experiences that matter in a decision-making context. Others’ experiences—some of which may be even more relevant to the issue at hand—need to be explored and considered. Sometimes, this means granting special privilege to groups and individuals whose experiences are particularly relevant.6 Open-mindedness refers both to the willingness to listen to the perspectives of others and the openness to being changed—or having one’s mind changed—through dialogue.7

- Empathy: Empathy is a broad term used often in educational literature. However, in the context of deliberation and deliberative democracy, it means something very specific. In this context, empathy “is not a feeling, but rather a process through which others’ emotional states or situations affect us.”8 A related term used by German social scientists is verstehen. This means to understand the meaning of an action from the point of view of the actor.9

- Political Friendship: Aristotle wrote that “friendship seems to hold states together” and that “the special business of the political art is to produce friendship.”10 Danielle Allen describes a particular kind of friendship—political friendship—this way: “Friendship is not an emotion, but a practice: a set of hard-won, complicated habits used to bridge differences of personality, experience, and aspiration. Friendship is not easy, nor is democracy.”11 This includes thinking about the consequences of a decision for members of the group who may disagree with or be adversely affected by it.

Fostering these traits in students is not easy. It requires repeated experiences with working together to solve common problems, critical self-reflection, and engaging imaginatively with the perspectives of others through film, literature, and dialogue.

As always, we encourage you to join the discussion of political friendship, discord, diversity, and democracy with your comments or questions below.

Related Post: Anger, Fear, and Polarization

Sources

Featured Image Credit: Walt Handelsman, New Orleans Times-Picayune

[1] NPR: https://www.npr.org/2020/10/27/928209548/dude-i-m-done-when-politics-tears-families-and-friendships-apart; The Atlantic: https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2021/03/trump-friend-family-relationships/618457/.

[2] Abramowitz, A. I., & Webster, S. “The Rise of Negative Partisanship and the Nationalization of U.S. Elections in the 21st Century.” Electoral Studies. 41. 12-22. 2016. Deichert, M. Partisan Cultural Stereotypes: The Effect of Everyday Partisan Associations on Social Life in the United States. Doctoral Dissertation, Vanderbilt University. 2019.

[3] Pew Research Center: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2022/08/09/as-partisan-hostility-grows-signs-of-frustration-with-the-two-party-system/

[4] Allen, Danielle. Talking to Strangers. University of Chicago Press. 2004. Parker, Walter C. Teaching Democracy: Unity and Diversity in Public Life. Teachers College Press. 2003. Hess, Diana, and Paula McAvoy. The Political Classroom: Evidence and Ethics in Democratic Education.

[5] Parker, Walter C. Teaching Democracy: Unity and Diversity in Public Life. Teachers College Press. 2003.

[6] Narayan, Uma. “Working Together Across Difference: Some Considerations on Emotions and Political Practice.” Hypatia 3.2. 31-47. 1988.

[7] Landemore, Helene. “What Does it Mean to Take Diversity Seriously? On Open-Mindedness as a Civic Virtue.” Georgetown Journal of Law and Public Policy. 16(S). 795-805. 2018.

[8] Morrell, Michael. Empathy and Democracy: Feeling, Thinking, and Deliberation. Penn State Press. 2010.

[9] Hannon, Michael. “Empathetic Understanding and Deliberative Democracy.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 101.3. 591-611. 2020.

[10] Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. Aristotle. Politics.

[11] Allen, Danielle. Talking to Strangers. University of Chicago Press. 2004.