“I definitely recommend this trip. It is a fun learning experience, and the memories I have made there I will surely never forget…You also get to hear different types of opinions from your group mates on government issues.” – Josie Smith

“I definitely recommend this trip. It is a fun learning experience, and the memories I have made there I will surely never forget…You also get to hear different types of opinions from your group mates on government issues.” – Josie Smith

“I definitely recommend this trip. It is a fun learning experience, and the memories I have made there I will surely never forget…You also get to hear different types of opinions from your group mates on government issues.” – Josie Smith

“I definitely recommend this trip. It is a fun learning experience, and the memories I have made there I will surely never forget…You also get to hear different types of opinions from your group mates on government issues.” – Josie Smith

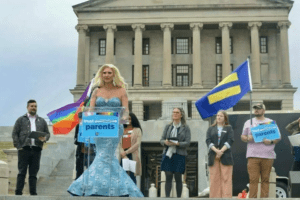

Last month, Tennessee Governor Bill Lee signed a first-of-its-kind law banning “adult cabaret entertainment” on public property or in any location where people under 18 could be present.

Senate Bill 3, commonly known as the “drag ban,” in part defines these performances as “male or female impersonators who provide entertainment that appeals to a prurient interest, or similar entertainers.”1 The law calls for first-time offenders to be charged with misdemeanors with subsequent offenses classified as felonies that could result in prison sentences of up to six years. The Republican-controlled Tennessee Senate passed the ban into law on March 2 with the intention for it to go into effect on April 1. The law was halted by a federal judge hours before it was to go into effect using a temporary restraining order, citing constitutional protections of freedom of speech.2

The drag ban has become a national conversation, with opponents of the law criticizing it for targeting the LGBTQ+ community. It follows several other issues considered by Governor Lee over the last couple of months, including prohibiting transgender Tennesseans from changing the gender listed on their driver’s license and prohibiting referrals for children to receive gender-affirming care in the state.3 Those opposed to the law are concerned that it is too vague in its definitions of what constitutes a “drag” impersonation and how to discern a location where a minor may be present. Both the American Civil Liberties Union and the Human Rights Campaign have expressed concerns that the law gives too much power to law enforcement to interpret the drag ban as they choose and potentially target transgender and gender-nonconforming entertainers performing in public.4

Members of the drag community argue that drag performances are much like any other form of entertainment. They say that just as some movies or comedy shows are appropriate for children and some are not, there are drag performances made appropriate for children and performances intended for adults. Performers are worried that authorities will not bother to discern the difference or will abuse the law in an effort to ban all drag performances.

State Senate Majority Leader Jack Johnson, a sponsor of the drag ban bill, argued on Twitter, “The bill gives confidence to parents that they can take their kids to a public or private show and will not be blindsided by a sexualized performance.”5 He continued, “We’re protecting kids and families and parents who want to be able to take their kids to public places. We’re not attacking anyone or targeting anyone.”6 While his sentiments were supported by most Republican legislators, Judge Thomas Parker—who ordered the temporary halt on the Tennessee drag ban and a Republican himself—felt the law was an overreach of government authority.

Regina Lambert Hillman, a professor of law at the University of Memphis, assured that the ban cannot prevent transgender persons from dressing as they choose in public. She explained in an essay, “You still have First Amendment protections, what that means is how a person dresses or what a person says, that does not change. The government cannot suppress speech, including expressive conduct, just because they find it offensive or they don’t like the content.”7

Though this law is the first of its kind passed, 14 other states have introduced similar legislation this year. Experts see this legislation as a coming trend that will likely cause similar conversations about whether it’s a First Amendment violation, LGBTQ+ rights, and how a law like this could be enforced. Meanwhile, the courts will be tasked with determining whether such laws are constitutional.

READ the full bill summary here.

Discussion Questions

Other Resources

Related Posts

As always, we encourage you to join the discussion with your comments or questions below.

Sources

There is a lack of public restrooms in America. It’s a problem you might only notice when you need to go. Those with chronic conditions such as gastrointestinal disorders, parents with young kids, and older Americans with weaker bladders may be most affected by this shortage, though anyone who just drank a large iced coffee can find themselves in need of—and struggling to find—a bathroom.

There is a lack of public restrooms in America. It’s a problem you might only notice when you need to go. Those with chronic conditions such as gastrointestinal disorders, parents with young kids, and older Americans with weaker bladders may be most affected by this shortage, though anyone who just drank a large iced coffee can find themselves in need of—and struggling to find—a bathroom.

A 2021 report by QS Bathrooms Supplies, a United Kingdom-based bathroom retailer, found that the United States had only eight public restrooms per 100,000 people.1 These are typically located in parks, by public transit, or in publicly accessible buildings, though they can be tough to find in times of emergency. Some people have taken it upon themselves to scope out and share locations of public toilets, like Theodora Siegel, who created a TikTok account that posts videos about free public bathrooms in New York City.2 She’s even crowdsourced an interactive Google Map with all the locations.3

The public restroom shortage means that the responsibility often falls to private businesses. When asked in 2002 about building more public restrooms, then-New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg replied, “Why? There’s enough Starbucks that’ll let you use the bathroom.”4 Though businesses, hotels, libraries, and museums have stepped up with “open-bathroom” policies to provide this public service, people may still feel obligated—or be outright required to—purchase a product or service to gain access to a toilet.5 And depending on the hours of operation, these bathrooms may not be available at certain times of day.

Public Toilets in the Past

America’s standalone public toilets date back to colonial times, when buildings had no indoor plumbing or dedicated “bathrooms” like the ones we’re used to. According to Debbie Miller, who serves as a museum curator at Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia, these public toilets were “common and generally communal” across the colonies; there was even an “octagonal outdoor toilet” located behind Independence Hall.6

At the turn of the 20th century, leaders of the temperance movement successfully advocated for the creation of public restrooms outside saloons in the hope that they would lead men to consume less alcohol in bars that had bathrooms.7 Throughout the Great Depression, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal public works programs built over two million “sanitary privies” in parks and “comfort stations” in cities across the country.8 By the 1970s, there were over 50,000 coin-operated pay toilets in America’s urban centers.9

The rise of the automobile and decline of downtown led to the closure of many public restrooms in train stations, bus terminals, and commercial districts.10 The New York City subway had 1,676 public restrooms available in the 1940s; by 2022, that number was down to a mere 78.11 Costly upkeep and strained budgets led to the removal of many public restrooms in subsequent decades, as toilets fell victim to vandalism and neglect.12 They were seen as dark and dirty, unsanitary and unsafe.

Private and Public Solutions

Public restrooms can cost anywhere from $80,000 to $500,000 to construct, and they require daily maintenance to keep them clean and functioning.13 Chad Kaufman, president of the Public Restroom Company which manufactures restrooms, notes that while cities “might have grant funds or public funds to build things, they typically don’t have operational funds to maintain these things.”14 The often glacial pace of government action means that it could take years to select a location, approve a plan, and design and construct the facilities.

The Council of the District of Columbia in 2017 passed the Public Restroom Facilities Installation and Promotion Act, which required a number of agencies to select sites and install public restrooms.15 It also required the mayor to “establish a financial incentive program to encourage private businesses to make their restrooms available to the public for free.”16 This sort of private-public partnership has been implemented in other countries like Germany and England, where local governments pay businesses a small stipend to promote their free toilets.17

In 2008, the city of Portland, Oregon, collaborated with a private manufacturer to design and install 24-hour, single-occupancy bathrooms called the “Portland Loo.”18 They have since been installed in dozens of other cities across the United States and Canada. China’s government led a directive, dubbed the “Toilet Revolution,” which constructed nearly 70,000 publicly accessible toilets in just two years.19 And in Tokyo, restrooms are designed to be vibrant works of art with bright colors, sleek designs, and “smart glass” that provides transparency and turns opaque when occupied.20

Prioritizing Public Restrooms

From a public health perspective, sanitation is crucial to well-being. An individual’s health contributes to the health of the community and the greater common good. When businesses were shuttered during the COVID-19 pandemic, we saw just how vital their bathrooms were to the public. When people don’t have access to a toilet—or a sink to wash their hands—germs and illnesses spread. Bathrooms also keep the surrounding areas of a community clean. They guarantee dignity to people who must meet their basic bodily needs. It can be humiliating to need the bathroom and not be able to go. People might risk arrest for public urination or end up soiling themselves because they couldn’t find one in time.

America’s restrooms should be easy to find, easy to use, safe, and comfortable. As communities improve their public spaces and upgrade their infrastructure, they should consider solutions that make sure their restrooms are accessible to all—regardless of disability, gender, gender identity, age, or socioeconomic status.

Discussion Questions

As always, we encourage you to join the discussion with your comments or questions below.

Sources